Bumps [zip](https://github.com/zip-rs/zip2) from 2.2.1 to 2.4.1. - [Release notes](https://github.com/zip-rs/zip2/releases) - [Changelog](https://github.com/zip-rs/zip2/blob/master/CHANGELOG.md) - [Commits](https://github.com/zip-rs/zip2/compare/v2.2.1...v2.4.1) --- updated-dependencies: - dependency-name: zip dependency-type: indirect ... Signed-off-by: dependabot[bot] <support@github.com>

Fornjot - Experiment 2024-10-30

About

This experiment is packaged as a single application. Run it with cargo run.

This should open a window and also create a 3MF file in this directory.

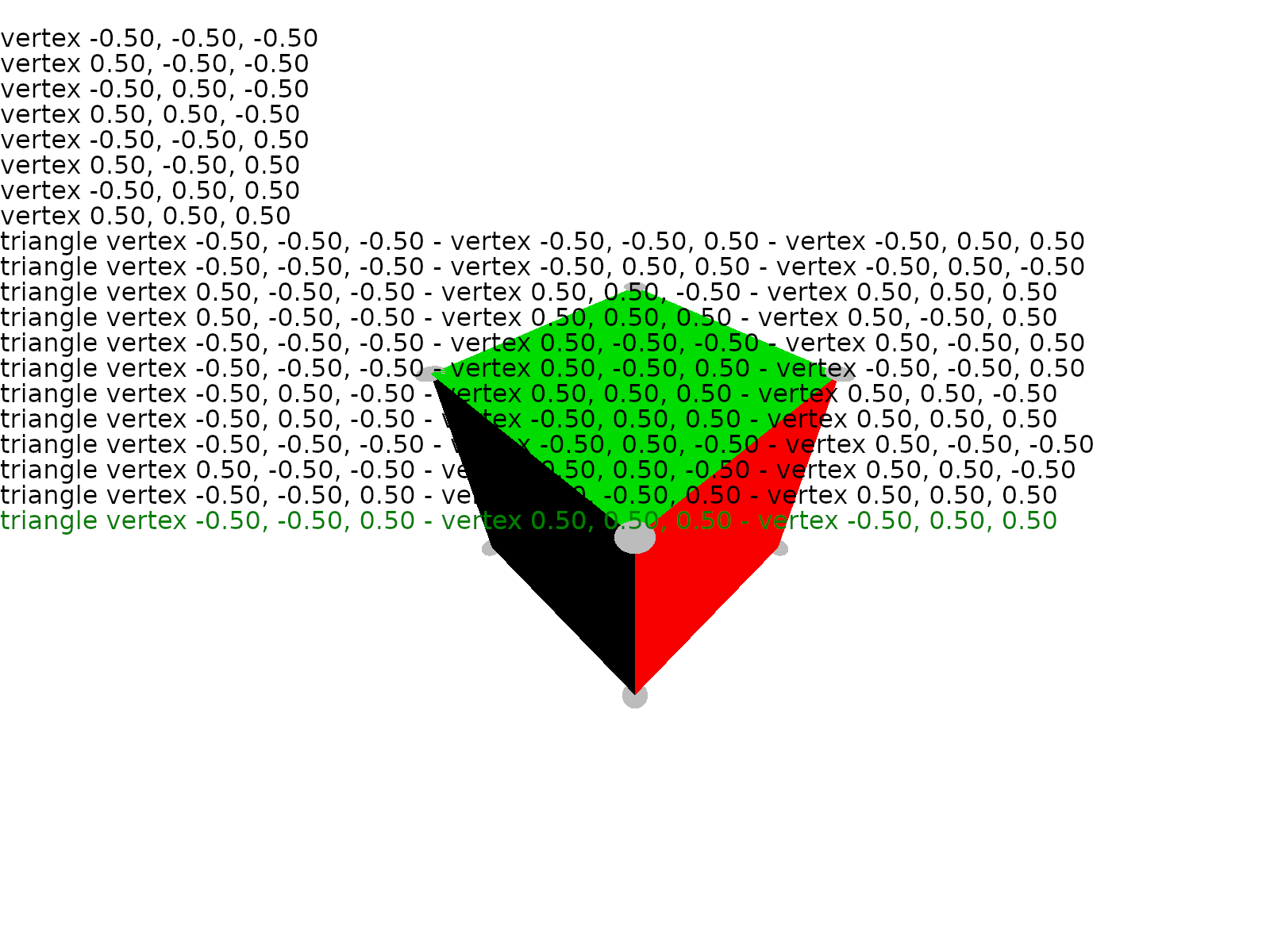

Once you started the prototype, you should see the hardcoded geometry in a background, and a list with operations in front. You can select other operations using the "up" and "down" cursor keys, which should display the geometry as of this operation.

Context

It has become clear, that Fornjot's current architecture is at a local maximum. I also think it is too complicated for what it does, and suspect that a simpler architecture would serve us much better going forward.

While it's certainly not impossible to address this piecemeal, through incremental improvements (which is the approach that I usually prefer), I don't think this is the best course of action.

Because while I don't consider the architecture to be very good, it is still consistent and self-reinforcing. Whenever I try to simplify one aspect, I run into the problem that it's there for a reason; that other aspects of the architecture depend on it being the way it is.

And while I haven't figured out yet, how to break out of this situation, I do have quite a few unproven ideas on how an improved architecture would look like, redesigned from the ground up using the experience I've gained over the last few years.

This experiment is intended to be the first in a series, meant to prove out those ideas. The results should provide a clearer picture of what is possible, and how the current architecture can be evolved.

Setup

I believe that one of the core mistakes that I made in designing Fornjot, was to design it as a batch system. API calls come in on one side, geometry comes out the other. What happens in between is not quite a black box, but it's not very transparent either. This is a big pain, whenever something goes wrong.

To kick off the upcoming phase of experimentation, I wanted to figure out what an interactive core could look like. One that allows you to see every single step taken to build up the final result.

I wanted to do this based on a very simple geometry representation, a triangle mesh, but with a view to later (in a follow-up experiment) expand that with a layer of topological information.

Result

I am generally quite happy with the result, although the experiment took longer than I wanted it to.

It wasn't clear that adapting the existing renderer to the needs of this prototype would be economical (I spent some time working on that, which made me think it wasn't), so I decided to write a new one. Most of the work went into that. I'm going to reuse it for follow-up experiments, and if this approach works out, I hope I can merge any improvements into the existing renderer.

Relative to that, very little work went into the interactive core. I came up with a design that I liked relatively quickly, so that was that. I'm not going to describe the results here, as I have documented the code instead.

If you're interested in details, take a look at the code itself, or check out

the documentation (run cargo doc --open in this directory).

Note: My writing process for the documentation in the code was a bit light on proofreading (which probably reduced the total effort to a fraction of what it would have been). I'm not sure how many people are actually interested in seeing all of the details, so I was more interested in putting down the information and moving on the next experiment.